The Sundarbans is a vast coastal delta and mangrove forest straddling India and Bangladesh, home to roughly 4.5 million people. This low-lying region sits at the mercy of the sea and mighty rivers, making its geography inherently fragile. Over the past century, the Sundarbans has steadily been losing land to the rising Bay of Bengal – an estimated 210 square kilometers have vanished since 1964 alone. Sea levels in the Sundarbans are rising at about 3 centimeters per year, more than twice the global average rate. Some islands are retreating as fast as 40 meters per year and a few have already been completely submerged. This encroaching sea not only swallows land but also pushes salty water inland, salinizing soils and aquifers. Large swaths of once-cultivable land have turned barren due to repeated inundation by saltwater, undermining agriculture and food security. Freshwater scarcity is worsening – in parts of the Indian Sundarbans, one study found 17 of 50 wells too saline for drinking– leaving communities struggling for safe water.

Deterioting Mangrove Cover

The ecology of the Sundarbans has historically provided a natural buffer. Dense mangrove forests help break cyclone winds and tidal waves, reducing erosion and flood heights. However, these protective mangroves are under strain. Between 2000 and 2020, roughly 110 km² of mangroves were lost (mostly to erosion) even as smaller areas have been replanted. Rising salinity and changing climate have also deteriorated mangrove health, with a shift toward more salt-tolerant but less diverse species. Deforestation and human pressures have weakened this green shield. The result is a landscape increasingly exposed to the full brunt of storms and sea level rise. Every year, high tides penetrate further inland, and seasonal river flows bring less replenishing sediment, compounding the erosion. In this way, the geography of the Sundarbans – low elevation, eroding coasts, and porous river channels – is fundamentally prone to climate hazards.

Human Vulnerabilities

Equally important are the human vulnerabilities layered onto this fragile geography. The Sundarbans communities are predominantly rural and economically marginalized. Millions rely on subsistence farming and fishing, supplemented by forest products like crabs and honey. Poverty is widespread, with many unable to meet basic nutritional needs. Health and education services are limited across the scattered islands, and infrastructure is rudimentary – mud embankments for flood control, thatch or tin-roof houses, and freshwater ponds for drinking water. This means any environmental shock can have outsized impacts. The culture of the Sundarbans has fostered a deep respect for nature’s balance (locals worship Bonbibi, the forest guardian, for protection), yet living “in the shadow” of the mangroves also means living with constant hardship. Taken together, the Sundarbans’ delicate ecology and socio-economic challenges create a perfect storm of vulnerability. Even minor climate perturbations can upset the balance of life here – and major disasters can be devastating. The stage is set such that when disasters strike, they strike hard.

Recurring Climate-induced Disasters

Life in the Sundarbans is punctuated by recurrent climate-induced disasters. Cyclones, in particular, have become an almost annual threat. Historically, about 13 significant cyclonic storms hit the Indian Sundarbans from 1961 to 2020 but in recent years the frequency and intensity have spiked. Scientists project that by 2040–2060, the frequency of severe cyclones in the Bay of Bengal could increase by about 50% as ocean warming energizes storms. This projection seems to be unfolding already. In the span of just three years around 2019–2021, four major cyclones struck the Sundarbans region, together killing nearly 250 people and causing nearly $20 billion in economic losses. Each storm brings its own horrors. Cyclone Aila (2009) was an early wake-up call – it killed over 300 people across India and Bangladesh and displaced half a million, revealing how unprepared the region was. A decade later, Cyclone Amphan (May 2020) became the strongest storm in decades, slamming into the Sundarbans with wind gusts up to 165 km/h and a storm surge of ~5 meters. West Bengal alone saw 86 deaths from Amphan, and damages were estimated at a staggering ₹1.02 trillion (approximately $13–14 billion).

The cyclone directly or indirectly affected about 70% of the state’s population – an almost unimaginable scale of impact. Millions of homes had roofs torn off and mud walls washed away; in total 2.8 million homes were damaged by Amphan across India and Bangladesh. In the cyclone’s immediate aftermath, entire villages of the Sundarbans were left in ruins – embankments breached, roads and jetties destroyed, electricity and communications down. Cyclone Yaas (May 2021) followed on Amphan’s heels, coinciding with seasonal high tides to inundate hundreds of villages. Though slightly weaker in wind speed, Yaas drove 6–8 foot tidal waves inland, swamping tens of thousands of mud houses and temporary shelters in West Bengal. Then in 2024 came Cyclone Remal, which made landfall over the Sundarbans delta; Remal killed at least 85 people (65 in India, 20 in Bangladesh) and knocked out power for some 30 million people in the broader region as transmission lines fell. These serial cyclones, combined with yearly monsoon floods, are the “recurring shocks” that Sundarbans communities endure with frightening regularity.

The Immediate Impacts

The immediate impacts of each shock are devastating. First and foremost is the loss of life and injury when storm surges and cyclone winds hit villages. Early warning systems and mass evacuations have thankfully reduced death tolls compared to past generations, but each cyclone still claims lives – often the most vulnerable caught in collapsing houses or swept away by floods. In material terms, a single cyclone can erase years of progress overnight. For example, Amphan’s destruction was so extensive that officials estimated 28% of the Indian Sundarbans was “destroyed” in one stroke– entire hamlets flattened by wind and waves. In Cyclone Aila, 778 km of embankments were destroyed, exposing farmland to the sea; billions have since been spent on repairs, only for Amphan to breach many embankments yet again. Critical infrastructure is often knocked out for weeks. After these storms, villagers commonly find their roads washed out, power lines down and drinking water contaminated. Cyclone Yaas, for instance, submerged low-lying areas in saline floodwater, breaking thousands of tube wells and latrines; roughly 19% of tube wells, 35% of ponds, and 43% of sanitation facilities were damaged by Yaas in the worst-hit parts. With wells clogged and ponds overtopped by saltwater, safe drinking water becomes scarce, heightening the risk of water-borne illnesses. In the days immediately following a cyclone, communities often face outbreaks of diarrhea and skin infections due to contaminated water and poor hygiene conditions. Medical and emergency services struggle to reach remote islands when jetties and boats are wrecked. Meanwhile, livelihoods take a direct hit: fishing boats and nets are destroyed, shops and markets leveled, and standing crops on the eve of harvest are wiped out. During Cyclone Yaas, entire fish ponds and rice paddies were spoiled by saline intrusion, and massive numbers of livestock and poultry were swept away, instantly robbing families of critical assets. The immediate shock leaves thousands of families homeless and without food or income, dependent on relief camps and aid for survival in the aftermath

The Lasting Impacts

Perhaps even more pernicious are the lasting impacts that linger long after the cyclone’s winds have died down. Each disaster sets off a chain reaction of long-term consequences for life, livelihoods, health, and social systems in the Sundarbans. One of the most visible long-term impacts is on livelihoods and food security. When storm surges push saltwater onto the fields, the soil can remain too saline for crops for years. After Cyclone Amphan, government assessments indicated over 100,000 farmers suffered heavy losses as their rice fields turned sterile and fish ponds filled with salt, rendering them unusable. Some affected fields have lain fallow season after season, directly undermining the food security and incomes of farming households. In many villages, repeated cyclones are eroding the traditional agrarian way of life – one study found that 62% of the workforce in several Indian Sundarbans villages has lost their original livelihood (farming or fishing) and been forced to seek alternative, often precarious, jobs. This economic dislocation contributes to a cycle of poverty. Families often must take on debt to rebuild or just to survive when their crops fail or boats are lost. Surveys after Cyclone Yaas showed a majority of affected households resorted to coping strategies like taking loans, selling assets, or reducing daily meals to weather the aftermath. Such measures provide only temporary relief but can trap households in debt and malnutrition, worsening their long-term prospects.

The Health Impacts

The Sundarbans already grapples with limited healthcare access, and disasters aggravate this. After major cyclones, there is often a spike in illnesses and a strain on health services. For example, in the wake of Cyclone Aila (2009), health surveys in remote Sundarbans hamlets recorded significant outbreaks of diarrheal disease due to the collapse of water and sanitation systems. Cyclones and the floods they bring create ideal conditions for water-borne and vector-borne diseases – standing water becomes breeding ground for mosquitoes (raising malaria and dengue risk), and broken sanitation leads to contamination of drinking water causing cholera, typhoid, and diarrhea. Longer term, repeated exposure to high salinity in drinking water has been linked to hypertension and skin diseases; on one Sundarbans island, 80% of villagers reported skin ailments from chronic contact with saline water. Malnutrition is another creeping impact – when crops are destroyed and livelihoods disrupted, families, especially children, face undernutrition that can cause stunting and other long-term health problems.

Moreover, mental health has emerged as a serious concern in these climate-stressed communities. The trauma of surviving each cyclone, coupled with the anxiety of living under the constant threat of the next one, has led to rising cases of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress. Local health workers observed surges in PTSD symptoms after Cyclone Aila, particularly among women who lost homes and loved ones. In recent years, mental health clinics in the Sundarbans have been reporting patients with recurring nightmares, insomnia, and panic attacks triggered by memories of past storms or fear of future disasters. Children are not spared – many experience terror at the sound of heavy rains and some refuse to attend school, afraid to be separated from parents during bad weather. This psychological toll erodes the social fabric over time, as fear and uncertainty become a part of daily life

Impact on Social Systems and Community Structure

Large-scale displacement is one reality: for instance, Cyclone Amphan alone displaced 2.4 million people in India at the height of the storm. While most were able to return after floodwaters receded, many thousands could not – their homes and land were simply gone. Prolonged displacement leads to the emergence of “cyclone refugees” living in temporary shelters or migrating elsewhere. Over the years, entire communities have been uprooted. Several small islands have vanished due to erosion and flooding, and an estimated 6,000 families had to be relocated when islands like Lohachara and Suparibhanga disappeared. Such displacement tears at community bonds and traditional support networks.

Migration from the Sundarbans is accelerating, often as a long-term adaptive response. With each disaster hitting livelihoods, more families send breadwinners to cities in search of work. It is estimated that roughly 60% of the male workforce from the Indian Sundarbans has migrated out to seek jobs in cities or other states. This leaves behind villages disproportionately populated by women, children and the elderly. While migration can bring in remittances, it also means fewer hands to rebuild after disasters and a loss of community cohesion. The women who remain shoulder greater burdens in both earning income and household care, even as they themselves are vulnerable

Additionally, the stresses of disaster and poverty can fray social cohesion – for example, human-wildlife conflict spiked after Amphan, as impoverished villagers entered core forests for resources, leading to more encounters with tigers. Such incidents underscore how recurring disasters can destabilize social and ecological balance, forcing people into risky situations.

Education and development also suffer: schools in the Sundarbans double as cyclone shelters, so frequent storms mean frequent school closures and damage to educational infrastructure. In 2020, Cyclone Amphan struck amid the COVID-19 pandemic, causing what was described as a “double destruction” to the education system – schools already shut for lockdown were then physically damaged by the storm. Many students lost months or more of learning and some never returned, dropping out to support their families. Each successive disaster thus undercuts long-term human capital formation and perpetuates intergenerational vulnerability.

In summary, the Sundarbans is caught in a relentless cycle of shock and recovery. Catastrophic events hit with alarming frequency, delivering immediate destruction and silently compounding long-term challenges. Lives and livelihoods are continually at risk, public health is persistently undermined, and the social fabric is strained by displacement and anxiety. These harsh realities highlight that responding to disasters after they occur is not enough – the impacts are simply too great and too enduring. The people of the Sundarbans are incredibly resilient, having adapted to difficult conditions for generations. But as climate change intensifies these shocks, that resilience is being pushed to its limits. Breaking out of this cycle requires addressing the root causes of vulnerability and investing in protection before the next disaster strikes. This is where the lens of Disaster Risk Reduction and Management becomes not just important, but truly life-saving.

Why DRRM is Crucial for Climate-Vulnerable Communities

For a fragile coastal region like the Sundarbans, Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM) is not just a policy buzzword – it is an existential imperative. DRRM encompasses the proactive strategies to prevent or minimize disaster damage (risk reduction) and to organize effective response and recovery (disaster management). In climate-vulnerable communities, it serves as the critical bridge between climate change adaptation and humanitarian response. The linkage is direct: as climate change fuels more extreme weather events, only a strong foundation in risk reduction can ensure that communities withstand these shocks without catastrophic losses. In the Sundarbans, where climate risks are escalating, building resilience is paramount. This means investing in measures now that save lives and livelihoods when the next cyclone or flood inevitably comes.

One clear reason DRR is crucial is to safeguard human lives and dignity. Decades of experience globally – and in nearby Bangladesh – have shown that early warnings and preparedness can dramatically reduce cyclone casualties. The Sundarbans has benefited from improved warning systems; for example, local authorities now evacuate tens of thousands of residents to cyclone shelters when a big storm is forecast, contributing to far fewer deaths than cyclones in past generations. However, staying alive is just the first step – people also need their homes and incomes protected to avoid chronic destitution. This is why DRR emphasizes protecting critical assets. Strengthened houses, embankments, and cyclone shelters are vital: retrofitting homes or building new structures to be cyclone-resilient (e.g. raised plinths, wind-resistant designs) can prevent families from losing everything in each storm.

Improved embankments and nature-based defenses like mangrove belts can shield villages from the full force of storm surges. For instance, wide mangrove buffers have been shown to reduce wave heights and can significantly cut the damage to inland communities, making ecosystem restoration a key DRR strategy. Likewise, ensuring there are enough robust cyclone shelters for all residents means people have a safe refuge and do not have to choose between risking the storm at home or overcrowding unsafe structures. Improvements to cyclone shelters and embankments, and expansion of mangrove cover, are cited as crucial steps to protect lives and reduce damage as climate events become more extreme. Each of these measures directly diminishes the impact of a disaster, which in turn means fewer injuries, less destruction of property and faster recovery.

Crucially, DRRM takes a systemic view of vulnerability. It’s not just about the hazard (the cyclone) but also about the community’s ability to cope. In places like the Sundarbans, vulnerabilities are interconnected: poverty, weak infrastructure, environmental degradation, and social marginalization all amplify the damage of any disaster. DRR interventions aim to tackle these root causes. For example, if lack of safe water makes post-disaster disease outbreaks worse, a DRR approach would establish resilient water supply systems (like raised tube wells or rainwater harvesting) before a disaster strikes. If over-reliance on a single livelihood (say, rice farming) means total collapse of income after a flood, DRR means promoting diversified and climate-smart livelihoods so that not everything is lost in one event. In short, investing in DRR is essentially investing in the long-term resilience of the community.

Studies in the Sundarbans have documented that adaptation measures without risk reduction can be futile: years of development gains can be wiped out by a few hours of cyclone destruction. For instance, after embankments were rebuilt post-Aila at great expense, Cyclone Amphan’s waves easily breached them again, showing that infrastructure must continuously be bolstered and upgraded in line with rising risks. DRR provides this forward-looking, preventive mindset, ensuring that development efforts (whether building schools, roads, or farms) incorporate risk mitigation features and are climate-proofed to the extent possible.

Another key reason DRRM is vital is the direct link to climate resilience. Climate resilience refers to a community’s capacity to absorb, recover from, and adapt to climate-induced shocks and stresses. Disaster risk reduction is, in practice, the toolkit for building that capacity. In the Sundarbans, resilience might mean a village that can endure a cyclone with minimal losses and bounce back quickly afterwards. How is that achieved? Through DRR measures: effective early warning systems that give people time to secure assets and evacuate, protective infrastructure (like embankments or safe shelter) that reduces physical damage, community training and drills that ensure everyone knows what to do, and contingency planning that positions relief supplies and contingency funds in advance. All these fall under DRRM and directly strengthen resilience. National policies recognize this synergy. India’s National Disaster Management Plan, for instance, emphasizes ecosystem-based approaches and risk reduction as part of climate adaptation commitments. In other words, protecting and restoring the Sundarbans’ mangroves (a DRR action) is also part of India’s climate strategy because it mitigates disaster impacts and sequesters carbon – serving both resilience and mitigation goals. Similarly, international frameworks like the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and the Paris Climate Agreement both call for integrating DRR and climate adaptation, especially for vulnerable regions. For the Sundarbans’ communities, building climate resilience on the ground translates to very tangible DRR outcomes: fewer lives lost, fewer homes destroyed, quicker recovery, and adaptation of livelihoods to withstand future shocks. Each cyclone or flood then becomes a test that the community can survive and recover from, rather than a catastrophe that reverses all development gains. Ultimately, disaster risk reduction is the path to a sustainable future in the Sundarbans – it enables these communities to thrive in place despite climate change, rather than being continually devastated or forced to abandon their ancestral lands

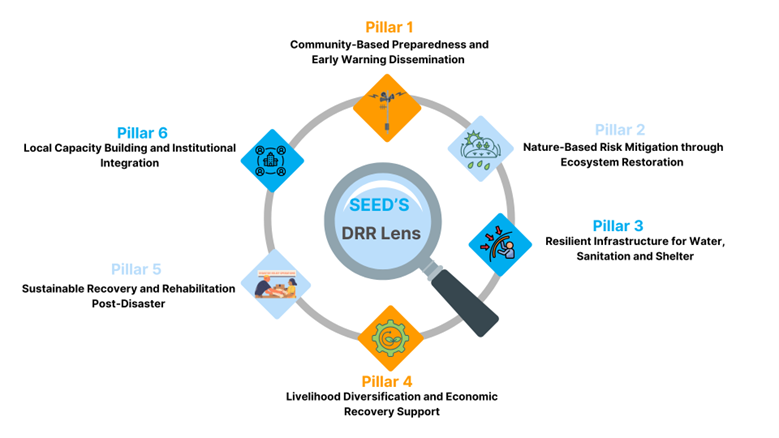

Drawing on over 25 years of engagement in the high-risk Sundarbans region, SEED’s DRR approach reflects the strategic vision of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, which emphasizes understanding risk, strengthening risk governance, investing in resilience and enhancing preparedness and recovery mechanisms. SEED’s six pillars—centered around community-driven preparedness, ecosystem-based mitigation, resilient infrastructure, livelihood diversification, sustainable recovery and institutional integration—form an operational blueprint that mirrors Sendai’s four priority areas in practice.

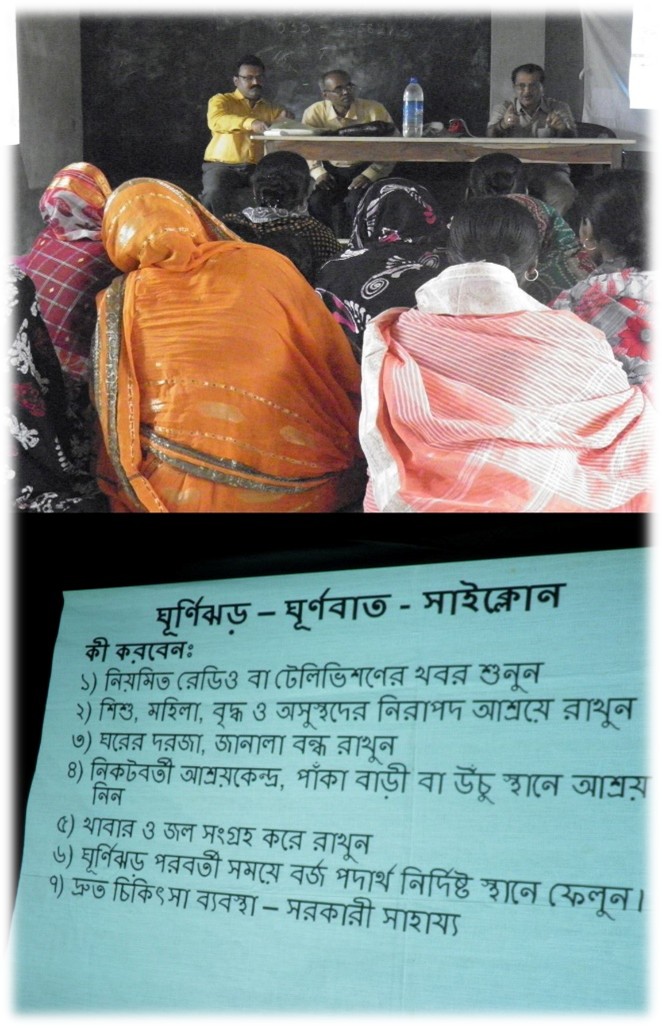

SEED’s Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) framework places strong emphasis on community-based preparedness, grounded in the belief that resilience must be built from the ground up. In a region like the Sundarbans—characterized by remote riverine islands, scattered settlements and often-inaccessible terrain—traditional top-down disaster communication models frequently fail to reach the most vulnerable. To bridge this critical gap, SEED has developed a decentralized, community-led preparedness model that ensures last-mile connectivity and rapid response, especially in high-risk zones such as Ghoramara Island.

Year-round, SEED works with local Disaster Management Committees (DMCs) and trains community volunteers to lead preparedness activities across villages. These trainings cover a wide spectrum of essential skills: securing homes and thatched roofs before a storm, creating waterproof document holders, designating livestock shelters, preparing emergency go-bags and understanding cyclone warning systems. The involvement of women and youth volunteers in these trainings ensures inclusivity and strengthens social cohesion in crisis situations.

One of the most impactful components of SEED’s preparedness model is its early warning dissemination system, which combines technology with local knowledge. During cyclone alerts, SEED activates a multi-channel communication strategy tailored to the socio-cultural realities of the Sundarbans. This includes door-to-door announcements by local volunteers, village loudspeakers, SMS alerts and community meetings. Such efforts have been especially critical in reaching elderly residents, persons with disabilities and women who may not have access to formal communication channels like mobile phones or television.

The effectiveness of this grassroots preparedness network was demonstrated vividly during Cyclone Remal in 2024. As wind speeds intensified and alerts were issued, SEED’s trained volunteers swiftly mobilized over 300 residents of Ghoramara, helping them safely evacuate to the Raipara Multipurpose Cyclone Shelter—a SEED-built facility elevated to withstand storm surges and equipped with solar-powered lighting. Notably, the evacuation was carried out with no reported panic, injury or delay, thanks to prior mock drills and detailed evacuation planning facilitated by SEED.

This model not only improves evacuation timelines and community response but also fosters a culture of collective action and resilience. By embedding disaster preparedness in the daily life of communities and leveraging local leadership, SEED transforms at-risk villagers from passive recipients of aid into proactive agents of safety. This grassroots architecture aligns closely with the Sendai Framework for DRR, which emphasizes the importance of inclusive, locally-driven early warning systems and preparedness education in reducing disaster losses.

Comprehensive Climate Education Programs

In the fragile and cyclone-prone landscape of the Sundarbans, SEED recognizes the critical role of ecosystems—especially mangroves—as natural buffers against climate-induced disasters. Mangroves act as the first line of defense, absorbing the brunt of high-velocity winds and tidal surges, thereby significantly reducing their impact on embankments, agricultural lands, and settlements. Drawing from this understanding, SEED has placed ecological restoration at the heart of its Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) strategy.

Through its flagship Community-Led Mangrove Revival initiative, SEED mobilizes local communities to restore degraded mangrove belts along eroded embankments, tidal creeks, and mudflats. This participatory model empowers villagers—many of whom have firsthand experience of the devastation caused by cyclones like Aila, Amphan, and Yaas—to become active stewards of their environment. By involving community members in site selection, plantation, and protection activities, the program fosters not only ecological regeneration but also a sense of collective ownership and long-term sustainability.

In addition to mangroves, SEED promotes embankment bioengineering by planting climate-resilient species such as Vetiver grass (Vitevar), which stabilizes soil, reduces erosion, and enhances water retention. These green infrastructure measures help arrest land degradation and protect freshwater ponds and agricultural plots from saline intrusion, which is increasingly common due to rising sea levels and storm surges. Since the health of soil and water systems is intrinsically linked to agricultural productivity, such interventions serve the dual purpose of risk mitigation and livelihood restoration

This ecosystem-based approach is in alignment with international DRR frameworks such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, which emphasizes nature-based solutions as a cost-effective, scalable, and sustainable means to reduce disaster risks. SEED’s ecological interventions, therefore, not only safeguard lives and infrastructure but also contribute to climate adaptation, biodiversity conservation, and community resilience—offering a holistic solution in one of the most climate-vulnerable regions of the world.

In climate-vulnerable geographies like the Indian Sundarbans, resilient infrastructure is not merely a development asset—it is a lifeline. SEED’s approach to DRR is deeply rooted in creating infrastructure that not only meets daily survival needs but also reduces risk exposure during disasters.

To address chronic water scarcity and contamination during floods, SEED has installed high-raised deep tubewells across multiple saline-prone villages. These tubewells are elevated on concrete platforms above flood levels (2.5 to 3 m) and are built to draw water from over 300 feet deep aquifers, ensuring potable water availability even when surface sources are rendered saline or inundated. During Cyclone Remal (2024), communities in Ghoramara were able to rely on these tubewells for uninterrupted access to clean drinking water, thereby preventing the outbreak of waterborne diseases and reducing pressure on relief operations.

In the flood-prone Sundarbans, community ponds are critical for freshwater access, yet they face recurring threats due to climate-induced disasters. Ponds are lifelines in these saline-affected islands, serving as key water sources household use, agriculture and aquaculture. During cyclones and heavy flooding, these ponds often get heavily silted, reducing their water-holding capacity, while their embankments—already weakened by years of neglect—are frequently breached, leading to further flooding of nearby homes and farmland. Recognizing these vulnerabilities, SEED adopts pond desiltation and embankment strengthening as core DRR strategies for water resilience.

By removing accumulated silt, the ponds regain their storage depth, ensuring availability of freshwater even during extended dry periods. Strengthened embankments—stabilized with climate-resilient vegetation or protective bunding—prevent overflow and erosion during cyclonic events. This dual intervention not only restores ecological function but also fortifies these water bodies as disaster-resilient infrastructure. Integrated with other water initiatives like high-raised tube wells and rainwater harvesting systems, SEED’s approach ensures that safe water remains accessible even in the aftermath of disasters, reinforcing both community resilience and long-term sustainability.

Shelter infrastructure is another critical pillar. In Raipara village, Ghoramara, SEED constructed a four-storey multipurpose cyclone shelter, designed with DRR parameters such as elevated plinths, reinforced concrete structure, and solar-powered backup systems. During Cyclone Remal, over 300 residents took safe refuge in this shelter. It also served as a base for emergency relief operations, proving its functionality as a hub for disaster response, training, and community mobilisation. Beyond its role in emergencies, the shelter acts as a community centre, hosting regular awareness sessions, health camps, and women’s group meetings, thereby fostering collective resilience and social cohesion.

Post-disaster economic fragility often leads to prolonged vulnerability, particularly in climate-sensitive regions like the Sundarbans, where livelihoods are intrinsically tied to land, water, and seasonal rhythms. Recognizing this, SEED’s approach to livelihood restoration emphasizes not just reinstating what was lost, but creating diversified, climate-resilient income sources that can withstand future shocks. Agriculture, the backbone of rural life in the region, suffers immense damage from saltwater intrusion, soil erosion, and irregular rainfall following cyclones. To address this, SEED has introduced salt-tolerant paddy and vegetable varieties in saline-hit areas, enabling farmers to resume cultivation with greater resilience.

Beyond agriculture, SEED promotes a mosaic of alternative livelihood practices that reduce the community’s economic dependency on any single sector. In various blocks across the Sundarbans—including Patharpratima, Namkhana, and Sagar—women and youth have been trained in homestead-based poultry and duckery, low-input aquaculture using brackish water species, beekeeping (apiculture), and water hyacinth-based handicrafts. These decentralized livelihood options are not only viable in post-disaster contexts but also build local enterprise and adaptive capacity. For example, after Cyclone Yaas, SEED established community-managed seed banks in Patharpratima block. These banks, stocked with climate-resilient seeds, enabled farmers to restart cultivation without delay, acting as a critical buffer between disaster and recovery

Skill-building interventions like handloom training, particularly targeted at women-headed households, also play a transformative role in livelihood diversification. Such efforts have allowed families to generate income even when agricultural activity is halted due to inundation or embankment breaches. Livelihood recovery under SEED’s DRR framework is thus not just about restoring income—it is about embedding resilience into the economic fabric of vulnerable communities. By equipping women and youth with viable skills and assets, SEED ensures a more inclusive and sustainable recovery that can absorb future climatic shocks while fostering long-term well-being.

SEED’s post-disaster recovery strategy transcends short-term relief, embracing a long-term, community-centered approach focused on rebuilding stronger, safer and more resilient lives and livelihoods. During major disasters such as Cyclone Amphan and Yaas, SEED has consistently mobilized emergency response within 24 to 48 hours—delivering life-saving essentials like food, tarpaulins, hygiene kits and drinking water to thousands across severely affected areas like Sagar and Ghoramara Islands. However, the hallmark of SEED’s approach lies in what follows this immediate response.

Sustainable rehabilitation begins with restoring shelters but not simply rebuilding what was lost. In Rudranagar Gram Panchayat, for instance, SEED supported 26 Lodha tribal families—among the most marginalized communities—in repairing their cyclone-flattened mud homes post Amphan. This was done with attention to disaster-resilient design and community participation. Recovery also extended to restoring livelihoods. In Patharpratima and Kakdwip blocks, over 350 farmers received salt-tolerant paddy seeds, allowing them to resume cultivation on saline-inundated fields—transforming despair into a renewed sense of purpose and food security.

Health recovery was addressed through camps like the one held in Ghoramara Island, where doctors treated over 150 residents suffering from skin conditions, worm infections, and cyclone-related injuries post Yaas. Simultaneously, psychosocial support and hygiene awareness sessions were held to address trauma and prevent post-disaster disease outbreaks, especially critical in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and Amphan strucking parallelly.

Water sources—crucial yet often contaminated post-cyclone—were revived or replaced with raised tube wells and rainwater harvesting systems to ensure long-term water security. Community members were also engaged in rebuilding embankments using local knowledge and labor, ensuring both ownership and sustainability of the efforts.

By transitioning seamlessly from immediate relief to long-term rehabilitation—covering housing, health, water and income—SEED ensures that communities not only survive disasters but are better equipped to face the next one. This continuum of care, rooted in dignity, local capacity and climate sensitivity, is the foundation of truly resilient recovery.

SEED invests in long-term DRR by building local institutions and linking them with formal disaster governance systems. Village-level disaster task forces are trained in evacuation, search and rescue and first aid. Women’s groups and youth clubs are oriented on their roles during emergencies. Schools are engaged through CEPA (Communication, Education, Participation, Awareness) sessions that embed climate education and disaster awareness in young minds.

Furthermore, SEED collaborates with Panchayats to integrate risk maps and preparedness plans into their development plans, aligning community actions with state and national DRR mandates. By creating local leadership and institutional convergence, SEED ensures that resilience is not just project-driven but deeply embedded in the community’s social fabric.

Subscribe to the SEED Newsletter — and be part of the change!